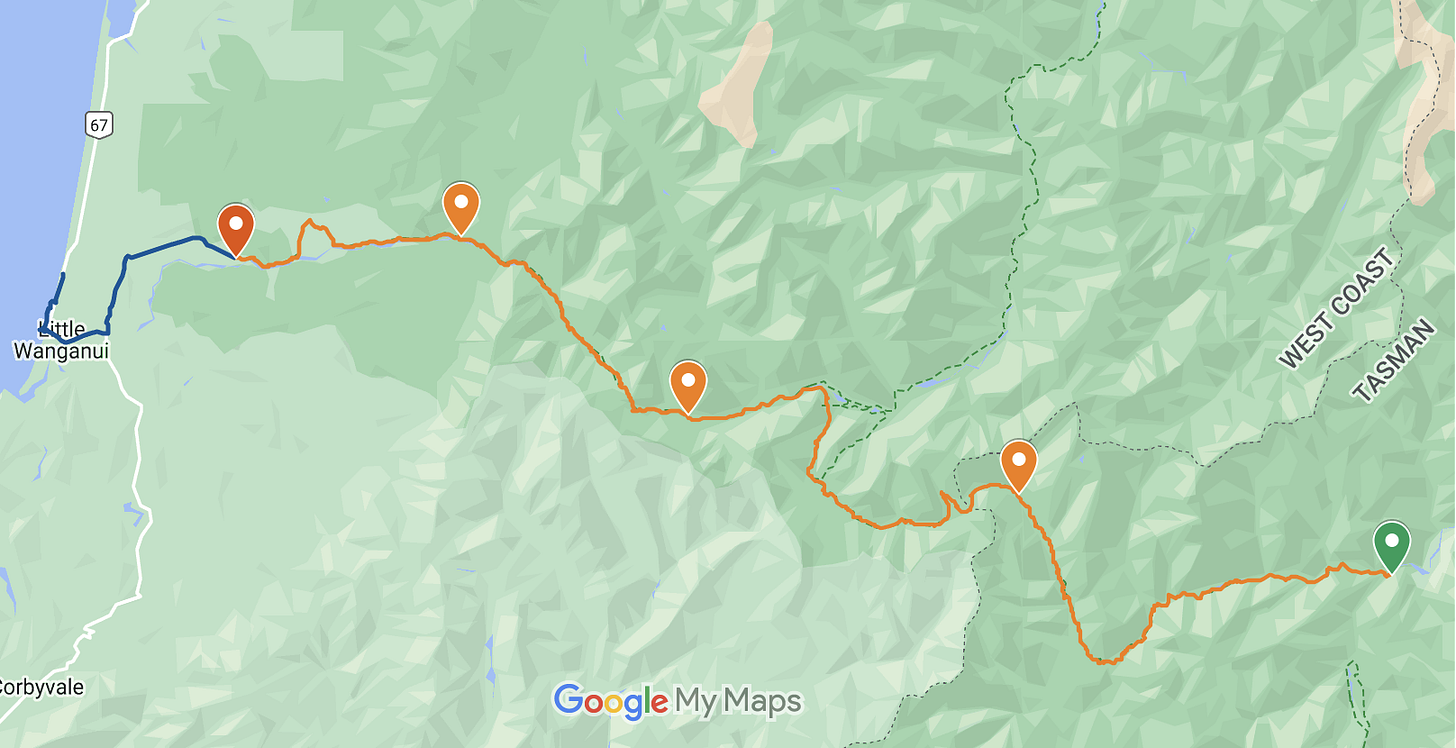

Four days hiking the Wangapeka Track

72.5 hours in the wilderness, following this historic New Zealand gold route.

The year is 1859 and someone has just sent word of the discovery of gold, using the WhatsApp equivalent of the time. Conversely to this period’s conventional findings, this rich stuff wasn’t on the West Coast. It was tucked up alongside a tributary to the Motueka River. It was in the Wangapeka River.

Work began on getting the gold out and - some three years later - unemployed gold miners began work on a route between Little Wanganui, on the coast, and the treasure rock. It was not fully finished until 1899.

The man in charge of the ‘track gangs’, as they were then known, was Jonathan Brough. I like to think they pronounced it “bro”. A prospector from Aussie, Brough was also a naturalist [double check that spelling, Dunc] and kept a diary of his time in the valleys overseeing the formation of the route. Unfortunately, his interest in nature also means he was likely responsible for spreading exotic seeds everywhere he went, possibly including large amounts of British stinging nettle.

“I’m sorry, but in lieu of any mānuka up these parts, at today’s smoko we’ll be sipping nettle tea. Thanks, Jonathan!”

I loves me a historic route, I do. Walking in the footsteps of others, taking your imagination back to a time when the people had less and had to scrape around in the dirt, hoping to win the Lotto of the era, is a great mind occupier. Any regular reader here will also know I adore the West Coast. Finding myself tucked up in Tapawera, I immediately made plans to walk the Wangapeka, some 125 years since its completion. Here’s how it went:

Day 1

Zoe drove me to the Rolling River confluence to pick up the track. Lazy, I know, but it’s 30km from Tapawera and road walking just ain’t the same. We parked up and a teenage family of weka came running down the hill to greet us. On the forage, they sniffed my kai-loaden pack, before playfully attempting to eat the bumper off Zoe’s car. Satirising kea, eh? This comedy troupe was the last time I saw weka hanging out as a bunch. On the track, they are solitary creatures.

Setting off, the track immediately takes you through a series of cleared flats. I can’t yet find any info about what used to be here or why they are cleared, but I like to imagine there was a small streetfront here, back in the day. You know, with a staging post, a livery, a blacksmith and a saloon. Or whatever the New Zealand equivalent was. It’s all blackberries and dandelions these days. Cheers, Brough.

The next feature on the track is the giant slip that dammed the river and created a lake in October 2012. DOC has all kinds of warnings about crossing this area and how you should move quickly to reduce the likelihood of meeting a falling rock, but I was more concerned about the rocks embedded in the ground turning my ankle bones into papier-mâché than anything up above. In fact, that was a theme for this entire adventure: watch your step!

The track continues up the valley, sticking close to the river, but often keeping it just out of sight, frustrating my efforts to catch a glimpse of any whiowhio. New Zealand’s rare blue duck is thriving in the Wangapeka Valley, thanks to the Whio Forever programme. I didn’t see any, though.

The first hut on the track is the neat, tidy and unremarkable Kings Creek Hut. Much more exciting is the ancient1 hut that once belonged to Cecil King, 15 minutes up the valley. From the pics I’d seen online, I presumed it to be a damp-infested, old wooden shed, with wasp nests for pillows. I gingerly opened the door, expecting to be scared witless and ready to run away, but found myself surprised at what I saw inside. It was beautifully restored; clean, tidy and only a few drafty gaps in the walls. It was more liveable than some of our country’s newer huts.

Another three or so hours up the valley separated the fancy, old shed and my first night’s sleep at Stone Hut. It’s a little 10-bunker, just below Wangapeka Saddle - the track’s first of two saddles over 1,000 metres in elevation. The infant river runs close by, providing water for cooking and drinking. 20km done, only some more to go!

Day 2

After Stone Hut, the track is no more. Officially, DOC classes the Wangapeka as a ‘route’ from here, but this is a fairly meaningless distinction, since slips and windfall still had reasonable diversions around them. In good conditions, these are never particularly difficult to follow.

Out of the hut, you’re soon crossing a major slip zone, which doubles as one of the more scenic sections around the saddle. The river quietly runs through a scrubby paddock of rubble, while the lack of trees reveals views of the surrounding slopes you wouldn’t overwise see.

The route re-enters the trees and climbs - sometimes steeply - up to and over the Wangapeka Saddle. This would be the highest point around here, were it not for the massive slip shortly after the saddle. Navigating this requires a climb back to the same elevation as the saddle and then some more. Still, it’s not long until you hear the roaring of Chime Creek. I saw a neat-looking camp site shortly before the creek. It seemed far enough from the water to be safe, with a sweet, flat patch of the green stuff - would love to know if you’ve stayed there!

You can ford the creek at low flows, or take the walkwire further upstream. I opted for the walkwire just for fun. The route then drops through the forest to meet the Karamea River, following it and crossing it several times, as you approach Helicopter Hut.

I took a late lunch at the hut, enjoying the sun blazing down, the lack of sandflies and the sound of the river bubbling by. I was half tempted to call it there and take a lazy lounge about for the rest of the afternoon, but I wanted to try and complete this journey quickly. Fast to the Coast, slow back.

Shortly before meeting the Taipō River, there’s a pause and a wooden, ramshackle monument to remember Jonathan Brough at the site of his hut: “Tabernacle in Wilderness”. He built the A-frame structure in 1898 and, according to the DOC info panel in Taipō Hut, it was still used by deer hunters in the 1960s!

The trail then descends to a swingbridge over the Taipō and enters a moss-filled, enchanted woodland. I stepped silently on the soft, mossy carpet, as the the sun glimmered through the tree leaves and the ultra-tame pīwakawaka pango (black fantails) came to greet me.

Eventually, I reached Taipō Hut, a monster 16-bunk dwelling in the bush. Far from either road-end, there was nobody there. I had the hut and its view of the Allen Range all to myself!

I dumped my pack and trotted down to the river for a bathe with the sandflies. Another 20km done.

Day 3

Every time I kip in a hut by myself, I have sleep hallucinations about somebody arriving late in the night. My stay at Taipō was no exception. I snoozed lightly, becoming convinced that the door had opened and a late arrival had softly walked in and made their bed. They really interrupted my sleep. Yet, I awoke in the early morning to find myself alone.

Today was the main event: crossing the Little Wanganui Saddle and spying the West Coast for the first time! I didn’t know it at the time, but everything else was just a warm up/come down to this. In the right conditions, it’s epic.

I trod on up the reasonable, but short, climb to Stag Flat where a small shelter sits. A lone weka met me outside, coyly begging for crumbs. The morning was still young and I suddenly fancied a coffee, so I stopped on a pebble beach of the small Taipō River and made one from its watery goodness.

Fuelled up and ready for the climb - which frankly looks near-vertical on the NZ topo map - I scrambled up to the saddle in a surprisingly swift 30 minutes.

And what views awaited: the beach, the waves, the forest and the mountains all collided in my senses. I felt so lucky. The day was perfect, for every other day, I only saw the saddle shrouded in cloud!

The steep descent from the saddle is rubbish. In part because you're leaving those views behind and in part because the low ferns block you from seeing hazards like slippery rocks and logs under your feet. It's slow going! Or you can go fast and just roll each ankle until they're shaped like shelving brackets. It’s your call.

The valley floor softens and you pass the emergency shelter bivvy with three names. Two signs on the small, two-bunk hut call it ‘Little Wanganui Gorge Shelter’ and ‘Wangapeka Emergency Shelter’, while the NZ Topo map labels it ‘Wangapeka Bivouac’. Having three names must be excellent in an emergency, when time and location precision are of the utmost importance:

“Where are you?”

“Err. Tell me which naming format you prefer and I'll get right back to you!”

I crossed the Little Wanganui River swingbridge, then parked up for a lunch, listening to the river crashing loudly down the large boulders.

Leaving the river for a spell, the track from here is superbly graded, for about five minutes. Windfalls and a bluff soon get in the way, forcing deviation from what would otherwise be a gentle, downriver jolly. Still, I enjoyed the flat trail relative to the saddle descent, making my way towards Belltown Manunui Hut - the hut that got moved a couple of years ago.

After what seemed like hours and hours and days and days, I rocked up at the hut... only to find it wasn't there any more. Ah yes, this was the hut that got moved a couple of years ago!

One kilometre more, my weary soul had to lug its bag. Twenty minutes later I reached the hut, in its actual place, a former site of multiple windfalls, carved up to create foundations for this tramper's inn. Another 12km in the biscuit tin!

Day 4

Before I set off, I glanced through the Manunui hut book, reading with interest the entries on Kākāpō Hut. With no marked track to it on the Topo map, I assumed it was just a chopper-in kind of place. Or maybe some canyoners could reach it, with ropes? Nope, it turns out a bunch of determined locals had gone and cut their own track to it! I parked that thought for my return journey.

The morning cloud cleared and the sun blasted the earth as I walked through the last truly native covered sections of the track and joined the flatter, road-like section through Gilmor Clearing. English grasses and nettles own the land, taking me back to Blighty. Bloody Brough and his wildfire seed-spreading!

After approx ten kilometres, a sign signifies the end of Kahurangi National Park. Then you're faced with a warren of tracks, driveways and properties, before you find yourself stood at the road-end. A DOC sign informs trampers what they are getting themselves into if they should pass it eastbound. I had walked the entire thing in 72.5 hours.

Roughly 2 hours' walk awaits those who choose to continue to the coast. I did. David and Archer from last night’s hut drove past and offered me a lift to Karamea, which I politely declined. I wanted to feel the West Coast surf on my feet knowing I had walked there on my own steam. However, Little Wanganui Hotel stood between me and the waves.

A plate of hot chips and a Monteith's Pilsner later, and I was stood in the clear water of the Tasman Sea. Magic! The hot chips were fantastic, crispy and soft at the same time; the aged jalapeño sauce option just the cherry on top: 9/10 (I never give 10s). Standing in the West Coast ocean on that hot, hot day: 10/10.

I guess I just gave a 10.

The Wangapeka Track itself can have a 10, too; just for the experience alone. It’s a true scramble through the wilderness, but with lots of pay-off along the way. Kahurangi National Park really is the jewel in the top of the South's crown.

What I’d do differently next time

1. Boots! I walked Wangapeka in a pair of Mammut Ultimate Pro Goretex approach shoes. I, wrongly, believed the speed I am used to hitting in trail shoes would be achievable on this track. If doing it again, however, I would definitely opt for a more rugged hiking boot. The route is littered with rocks and when it’s not, it’s entangled in tree roots, many of which you can’t see due to the low-grow flora.

2. Sprint. If going for speed, I think it’s possible to tear through in two long days, just spending the one night en route - probably at Helicopter Hut, or possibly Taipō. The reduced food load would offer considerable weight savings, enabling you to travel further faster.

3. Gaiters. This could be the trail that converts you to gaiters, if you’re not a user already. There’s enough river fording, mud, hook grass and, in summer, wasps to tempt bare-legged adventurers over to the covered side.

In New Zealand terms! Save your complaint letters.